As has been discussed in previous blogs, time management is a critical factor of dissertating. However, though many people think the best way to be productive and use time wisely is to continuously work on their dissertation, that may not always be the best course of action. Though it seems contradictory, it may end up saving you time if you know when to sit back and wait, as well as when to take action.

One frustrating part of the dissertation process is waiting for feedback. The dissertation goes through so many rounds of review and revision, many people feel that they are wasting time sitting and waiting to receive drafts back from their chair, committee, URR, and form and style reviewers. Before deciding to put your time to use working on your dissertation while awaiting feedback, it is important to consider who is currently reviewing your draft, what sections they are reviewing, and what sections you would like to work on. Never work on a section or chapter while someone at your school is reviewing it. Doing so unnecessarily increases the risk for increased revision and time spent. Further, it is often in your best interest to hold off on working on sections that require any sort of school approval before you have received it. This is especially important for data collection, as approval from your committee, school, and Institutional Review Board is required before you can begin this step.

However, some things can be great to work on while you wait. Things like literature research and annotating sources can often be done while a draft is reviewed. Even though many things may change in your dissertation as a result of reviewer feedback, the general topic will likely stay the same, and thus the literature you use will still be relevant. Preparing for your oral defense presentation is also helpful, as you can create your visual aids while you wait and start practicing your presentation while awaiting feedback. If something changes based on the review, all you have to do is update your presentation accordingly. These are great ways to stay engaged in dissertating while waiting for reviews to finish. However, if the things you need to work on next require guidance or approval, or are currently under review, that is an appropriate time to sit back and wait.

Sometimes when dissertating, waiting really is the best call you can make. However, if there are sections you can work on while someone is reviewing parts of your dissertation, it can be beneficial to do so. The dissertation is a long process, so it may be that there are things you can work on while you wait. They key is to be thoughtful about what sections are being reviewed and what you can work on while you wait, because you never want to create more work for yourself.

After you have collected the interview data for your qualitative dissertation, you will need to transcribe these data. You may even think of transcription as the first step in a qualitative data analysis, because as you are transcribing you are immersing yourself in the data and becoming familiar with your participants’ narratives. Many academic transcription services exist, but because the transcription process is so important for understanding your data set, you should consider doing this yourself. The transcription process requires time, so prepare yourself mentally for this endeavor. Experts suggest that for each hour of audio-recorded interviews, expect to spend 3-4 hours transcribing. This will take even longer if you are also translating from one language to another.

You may find it helpful to review the audio-recordings of your interviews before setting pen to paper (or hand to keyboard). This will give you a flavor of the arc of the interview and help you anticipate what is coming when you begin transcribing. If you need to review the recordings multiple times, you should do this. Think of this as immersing yourself more deeply in the data.

Efficient methods for transcribing interviews

There are different ways to transcribe interviews. One way that you could do this is with a blank word-processing document and your audio-recording device.

Press play on the recorder and begin typing, transcribing verbatim what both you as the interviewer and what your participants said. Depending on your specific analysis, you may also record utterances such as pauses and hesitations. When you need to stop, press pause on the playback. If you missed something, you can rewind and go back. If this seems unwieldy, there are other options. One option is using a foot pedal. New and used foot pedals designed specifically for transcribing interviews are available for under $100. These connect to your personal computer via USB and come with software that helps with transcription. You will transfer the audio recordings from your interviews onto your computer, and then as you transcribe, simply press the foot pedal to pause and play the recording! There are also internet browser add-ons that can assist with transcription. Some cost a small fee, but they allow you to work entirely in a web browser and are operated through the use of hotkeys, meaning you never have to take your hands off the keyboard.

When all of your interviews are transcribed, you will want to re-read your transcripts as you listen to the recordings, watching for any errors in transcription. This is your chance to correct any mistakes that you may have made in your transcription. If you plan to use member checking, now you have a complete transcription to give your participants. After all of this is completed, you will be ready for data analysis!

If you are conducting research on a specific population, you will want to make sure that your sample of that population is representative. If your sample is representative of your population, you will be able to confidently generalize the results of your study to that population. But what exactly does that mean?

First, let’s review the difference between your population and your sample, as many students often get these terms confused. Your sample is the group of individuals who participate in your study. These are the individuals that provide the data for your study. Your population is the broader group of people that you are trying to generalize your results to. So, for example, if you wanted to determine the relationship between gratitude and job satisfaction in shark biologists, your sample might consist of 30-40 individual shark biologists. Your population might be “shark biologists in the United States,” or, if the scope of your study was more narrow, “shark biologists in Florida.”

A representative sample is one that accurately represents, reflects, or “is like” your population. A representative sample should be an unbiased reflection of what the population is like. There are many ways to evaluate representativeness—gender, age, socioeconomic status, profession, education, chronic illness, even personality or pet ownership. It depends on your study’s detail, scope, and available population data.

So, if most shark biologists in the population are women, but your sample is all male, you do not have a good case for representativeness because your sample does not share the same characteristics as the larger population. You cannot generalize the results because your sample differs significantly from the population.

Need help conducting your analysis? Leverage our 30+ years of experience and low-cost same-day service to complete your results today!

Schedule now using the calendar below.

Lack of representativeness often comes from sampling errors or biases. Sampling error occurs when surveying dairy consumption at a popular vegan café. Another example would be studying the drinking habits of college students, but only sampling from members of fraternities. In these examples, it is easy to see how the characteristics of the samples may potentially bias the results.

So, how do you avoid sampling error and select a representative sample? First, thoughtfully consider your sampling frame (your possible participants) and recruitment procedures. Avoid recruiting only a specific subset, like fraternity members or vegan café-goers. Next, a good way to reduce bias in sampling is to randomly sample from your sample frame. Through this, you minimize any selection biases that might occur, such as volunteer bias. You also can implement a stratification protocol, such as proportionate stratified sampling. Let’s say you do your research and find out your population of shark biologists are 80% women. You could then make sure that 80% of your sample consists of women, such as by quota sampling. Consider sample size; larger random samples are usually more representative.

Finally, keep in mind that its unlikely that every sample will be perfectly similar to population of interest. There will always be a little sampling error associated with any study, unless you sample every single member of your population.

Using the more advanced features of Microsoft Word, such as the References tab and caption or cross-reference functions, can seem a bit daunting, especially for those who have never had to create an automated, linked list before. However, creating a linked List of Tables at the beginning of your dissertation document will provide increased ease-of-use and functionality. Most universities require a List of Tables at the beginning of the dissertation, because this function allows readers to Ctrl + Click on a Table in the list and be automatically directed to that table in the text. In addition, if the writer needs to add a table or update the page numbering, it can be as simple as a right click!

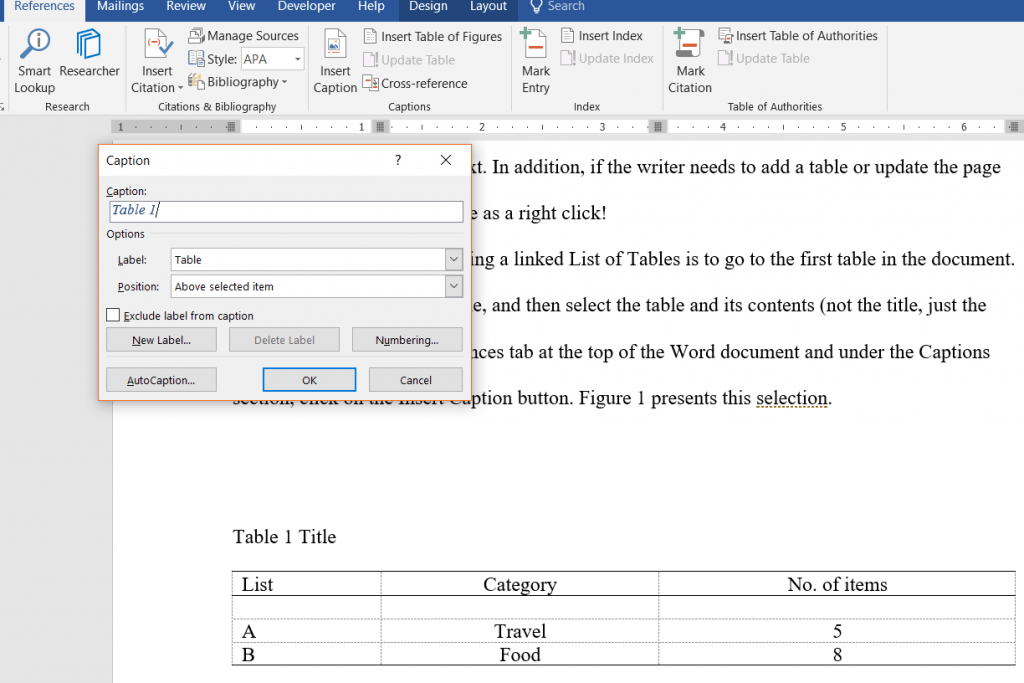

The first step to inserting a linked List of Tables is to go to the first table in the document. Next, copy the title of the table to your clipboard, and then select the table and its contents (not the title, just the table). Then, go to the References tab at the top of the Word document and under the Captions section, click on the Insert Caption button. Figure 1 displays this selection.

Need assistance with your project? Leverage our 30+ years of experience and low-cost service to make progress on your results!

Schedule now using the calendar below.

Figure 1. Insert a caption on a table.

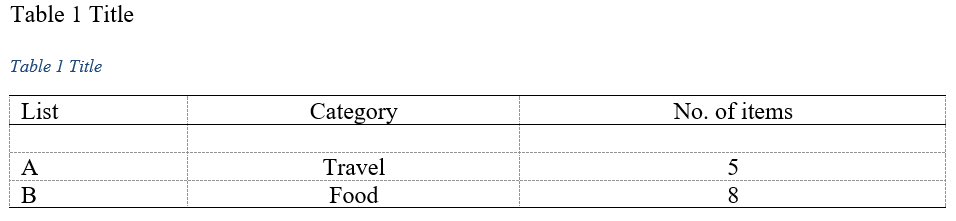

In the Captions box that appears, type or paste the title of the table after the word Table and then click OK. A new Table and Title will be inserted above the table (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. New table title inserted.

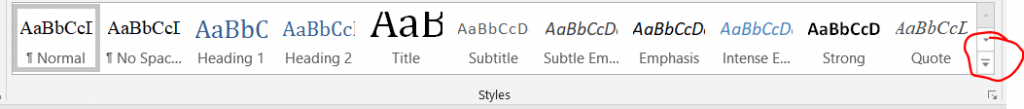

Next, you will need to modify the caption text so that it matches your university or style guide requirements. Following APA, this should be Times New Roman 12, double spaced, black font. To modify the caption, go to the Home tab at the top of the Word document. Under the Styles menu, at the far right, click on the drop-down arrow to select Apply Styles… (see Figure 3). You can also open the Apply Styles menu by pressing Ctrl + Shift + S on the keyboard. A styles menu should appear on the screen, usually to the left.

Figure 3. Styles menu drop-down, located under the Home tab.

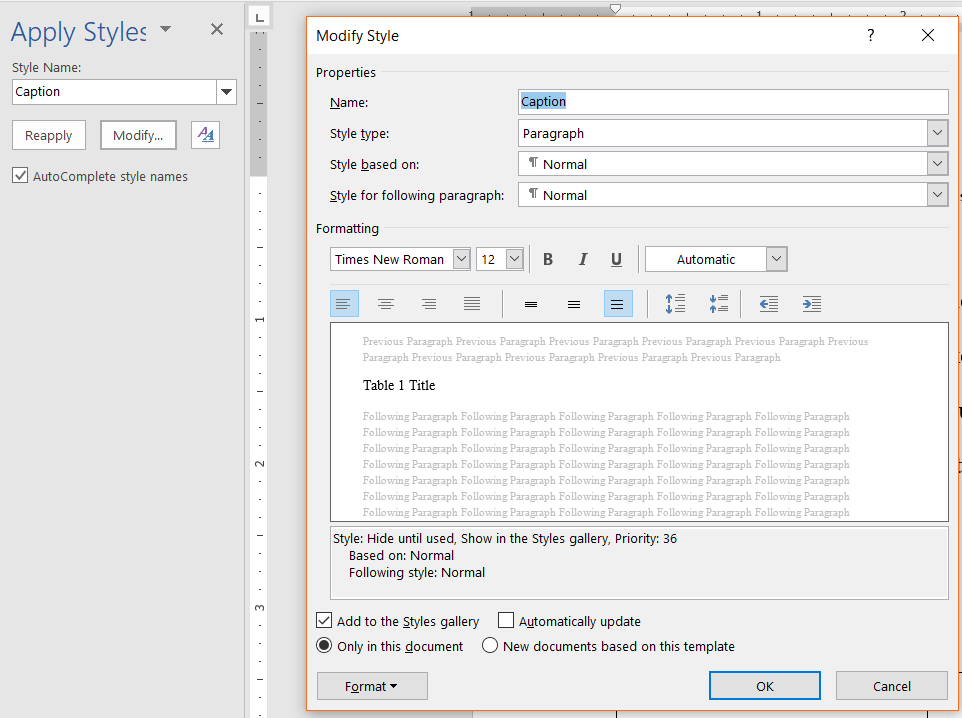

Next, place the mouse cursor in the table title caption, and the Style Name “Caption” should appear in the Apply Styles menu. Click on the Modify… button and select the appropriate formatting for the caption. Figure 4 presents an example of this. After you have adjusted the font style formatting, select OK. From this point forward, every time that you insert a new table title or caption. Then, it will automatically format correctly to how you modified the Caption style.

Figure 4. Menu to modify the caption style.

Now that the laborious part of modifying the caption style is complete, simply continue inserting captions to all subsequent tables in the text. You will repeat the process from the beginning: copy the table title, select the table, click on the Insert Caption button under the References tab, and then paste or type the title of the table and click OK. Make sure to delete any old table numbers or titles, as the Insert Caption feature creates a new one.

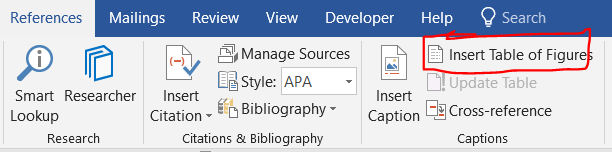

After all table titles have been linked and inserted with the Caption style, return to the preliminary page in your document where you would like to insert the automated List of Tables. Next, go to the References tab and this time select the Insert Table of Figures button (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Insert Table of Figures option under the References tab.

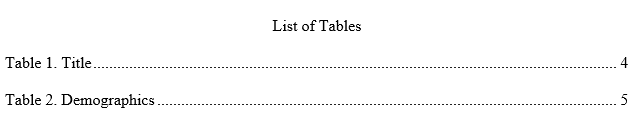

Before selecting OK, you can also click on the Modify button and change the formatting of the List of Tables, if needed, to comply with your university guideline requirements. After selecting OK, the List should appear similar to the following:

To update the List of Tables, you can simply right click on the list. Select Update Field, and then choose either Update page numbers only OR Update entire table. The only reason you would need to update the entire table is if you altered any part of a table title. For example, capitalization of a word or if you added (and linked with a caption!) a new table. Microsoft Word will automatically repopulate the page numbers and table information for you.

This step-by-step tutorial provided the basic explanations of how to link tables in a document with a caption style. Also with a automatically insert and populate a List of Tables. Following these steps will alleviate the time spent trying to manually create a List of Tables. This will also allow readers to quickly navigate the document to view tables in the text.

Securing participants for your study can be challenging. Often, potential participants do not think the indirect benefits of participating in a study are worth the time they will spend in the study. Offering a direct benefit or incentive for participation may help increase participants’ willingness to take part in your study.

Compensation may take numerous forms such as gift cards, money, or other benefits. Identifying a monetary or non-monetary benefit for participation and providing compensation that aligns with your participants’ interests may increase your participation rate. However, it is important to offer compensation without undue inducement.

Undue inducement refers to compensation that is so great in amount or nature that it decreases participants’ ability to rationally consider participation in the study (Wilkinson & Moore, 1997). For example, if you are studying a population of severely economically disadvantaged individuals, a $100 grocery gift card may be considered undue inducement. If $100 can mean the difference between putting food on the table or going hungry, such an incentive can be considered coercive. People may feel compelled to participate if the compensation will significantly impact their physical, psychological, or economic well-being; this, in turn, compromises the voluntary nature of the study.

To avoid this, you should consider offering compensation that serves as a token of appreciation or reimbursement. This token should be intended to thank participants for their time or to reimburse them for any costs they may have had to endure (e.g., the cost of gas if they have to drive themselves to the study site). The compensation should not be so large that individuals may feel compelled to participate. In the example above, a $5 gift card may be considered an appropriate level of compensation without risking undue inducement. Just remember that, above all else, potential participants should see your study as a voluntary activity, and you should not offer any incentives that might change that perception.

Reference

Wilkinson, M., & Moore, A. (1997). Inducement in research. Bioethics 11: 373-389.

Many doctoral students view their committee as an obstacle in the dissertation process. While some committees may seem difficult to work with, it is important to remember that they are appointed to provide you with guidance. You should build rapport with your committee members early on in the process. Do research on each professor’s academic focus and review their publications. Identify each committee member’s preferred means of communication and consistently use this method. Determine if they prefer to use tracked changes, highlights, or change matrices to keep track of revisions.

Develop a road map for the dissertation journey and set clear goals and time lines. Ask for sample papers that have been approved from the school so there is a general template to follow. Touch base with your committee at regular intervals to provide updates or discuss issues; we recommend weekly meetings or check-ins. Determine the sections of the paper that each committee member will reviewing specifically. Typically, universities provide a literature review specialist (sometimes referred to as a “subject matter expert”) and a methodologist. If uncertain of a theory or methodological approach, notify the appropriate committee member so they can provide suggestions. Because the dissertation can be a lengthy process, all of your communication with your committee and school should be saved, if possible, so you can review it in the future. Have the committee double check all permission forms, consent forms, and survey questions. An extra set of eyes can help detect lingering spelling, grammar, and formatting issues.

These are just a few suggestions for how you can effectively collaborate with your committee members and make the dissertation process go more smoothly!

Every study that has ever been conducted, or will ever be conducted, has limitations. Identifying the limitations inherent to your study is not only an important part of the research process, but also important for future researchers to consider in framing their studies. Although anyone well-versed in research expects you to acknowledge weaknesses of your research, there is an art to describing these potential issues without devaluing your research. In fact, showing results of an analysis with due diligence given to identifying your limitations helps future researchers frame their studies and form a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. In this blog, I will outline a few ideas to get your limitations section started.

Sample Size Limitations: The number one most common limitation to doctoral level research is sample size. Most often this limitation surfaces during data collection, though sometimes researchers may know early on that their sample will be either limited or difficult to solicit. Most quantitative analyses require a fairly large sample, and without funding to compensate participants, there may be little you can do to encourage more people to participate. Reduced sample sizes make p-values stray from significance, and this may be used to justify why you might not find the results you expect. You can explore the effect of this limitation more through post-hoc power analysis; sometimes it does not present a problem but can still be listed as a limitation!

Generalizability or Sampling Limitations: Another common limitation has to do with the degree of generalizability. For example, if your study data consisted of small business owners from the Midwest U.S., the results that came from these data might not translate to owners of larger businesses or small business owners outside of the Midwest. You can justify this based on your scope (i.e., maybe the purpose and problem of your study are only relevant to this population in particular) or you can use your findings as a springboard to suggest future researchers look at different populations given the evidence from your study.

Resource Limitations: Finally, many researchers also run into limitations regarding resources. These limitations can be in reference to time, access to participants, or even the fact that there is no good instrument for measuring your study’s concepts of interest. In many cases, doctoral-level research is not funded, and students are required to adhere to short timelines; both of these factors can be discussed your limitations section. Just be sure to explain how the lack of time or funding impacted your research. I already mentioned that not being able to provide compensation to participants may result in a smaller sample. Another example of a resource limitation might be that you wanted to administer some kind of treatment or intervention for four weeks, but you could only follow through with two weeks in order to meet your institution’s deadlines.

When describing your data collection and data management procedures for research involving human participants, you will inevitably need to discuss anonymity and confidentiality. These two concepts are especially important to consider as you apply for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, as the IRB will want to ensure that you are taking appropriate precautions to protect participants. However, many students struggle to properly differentiate anonymity and confidentiality and often use these terms interchangeably. So, what exactly is the difference between the two?

Anonymity means that there is no way for anyone (including the researcher) to personally identify participants in the study. An anonymous study cannot collect personally-identifying information, such as names, addresses, emails, phone numbers, government-issued IDs, photos, or IP addresses. Additionally, any face-to-face or phone-based study is not anonymous, excluding most qualitative research with interviews.

Online surveys are common for anonymous data collection, but not all are truly anonymous. If researchers track email or IP addresses, privacy is lost. Sometimes IRBs will require that participants have a way to withdraw their survey responses. In these cases, collecting a personal identifier such as an e-mail address may be inevitable. Additionally, depending on the study’s sample frame, surveys that collect several pieces of demographic information may not be truly anonymous. For example, in a company sample, demographics like age, gender, ethnicity, or tenure could identify participants.

Need help conducting your research? Leverage our 30+ years of experience and low-cost same-day service to make progress on your results today!

Schedule now using the calendar below.

Confidentiality allows participant identification, but only the researcher knows their identities and keeps them undisclosed. Proper data management and security best ensure confidentiality. Researchers use ID numbers (quantitative) or pseudonyms (qualitative) to keep identities separate from data. They must follow IRB-required security measures, including locking paper data, password-protecting electronic data, and securely destroying it after research completion.

Whether anonymous or confidential, inform participants about the data collected and identity protection. Include these details in the consent form to ensure privacy.

So, you have worked your tail off to dig deep into the literature to find what you hope will fill over 40 pages of your monstrous Chapter 2. Now what? Well, ideally, you will begin crafting a clear and concise synthesis of the literature. However, oftentimes dissertation candidates struggle with putting it all together. A good place to start (and an easy box to check off for your chapter) is with writing the Literature Search Strategy.

This particular section in your Chapter 2 is really a plug-and-play piece. There are two main things that you focus on in this section. The first one is the databases that you used to locate the articles that you found, and the other is the search terms that you utilized. A secondary, minor, element to this section is the date range of articles searched. Most schools have a five year limitation for non-seminal pieces. Once you have these elements, you can craft something like this:

The search for current, 2013-2018, peer-reviewed articles was conducted via the online library. These databases included Academic OneFile, Academic Search Complete, ERIC, Gale, JSTOR, Sage Journals, and PsycNet . Google Scholar was also utilized to locate open access articles. The following search terms were used to locate articles specific to this study: drug abuse, drug treatment, and so on. . Variations of these terms were used to ensure exhaustive search results.

Using the template above, you should be able to quickly and easily knock out this section of your Chapter 2!

We are rebranding Statistics Solutions as “Complete Dissertation by Statistics Solutions.” While our company has always been a full-service dissertation editing company for both quantitative and qualitative dissertations, the Statistics name was a bit confusing for those doing qualitative research, and those of you looking for assistance with chapters 1,2,3, and 5 of your dissertation. To see a full list of our services click here.

Why do we do what we do? The reason is simple. Many students never graduate and are left with a mountain of debt (I’ve heard over $300,000 once). Our contribution is to use our core expertise to ethically edit students work and support them in the process without them incurring even more debt and spending another birthday wishing they had completed their dissertation. Let’s face it, some of the schools don’t have it together, faculty leave (leaving the student to start afresh with another advisor), and life happens to students too. I believe some students are unprepared and need just a little bit of hand-holding. We can help!

We believe in ethical support. We don’t believe that students should have to take extra classes, “refresh their literature review,” and that taking a class 3 years ago is not sufficient to tackle the some of the dissertation tasks today.

Consider a Free 45-minute consult to explore how ethical support can help you!

Best,

James Lani, PhD

(877) 437-8622